Adventurers: Beachcombers

Castaways and mediators

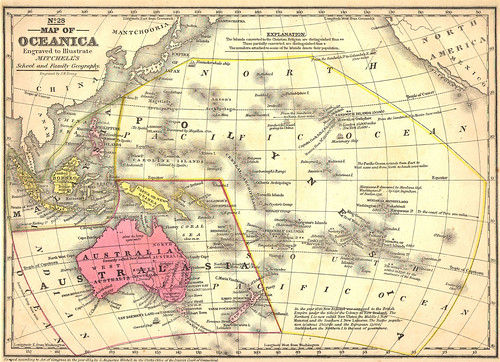

In the Pacific, no other group of people was more reviled than the beachcomber. Considered degenerate characters, they have been charged with infecting islanders with whom they lived with a moral disease deemed more destructive than smallpox or influenza. A motley crew of deserters, convicts, castaways, and those simply with wanderlust converged in and among many islands of the Pacific—primarily islands in Micronesia and Polynesia; Melanesian islands were feared due to cannibalistic rites—during their 19th-century heyday. Although their reputation as rogues and scalawags may be deserved, there were positive contributions beachcombers made to island communities and to Euro-American traders.

The very first European beachcomber of record lived on Guam for four years among the CHamorus. On 4 September 1526, Padre Garcia Jofre de Loaysa anchored at Guam for a four-day stay to replenish ships’ stores. Welcoming the Loaysa expedition was Gonzalo de Vigo — a cabin boy on one of Ferdinand Magellan’s ships, the Trinidad — who had jumped ship four years earlier. De Vigo was taken aboard Loaysa’s ship bound for the Philippine Islands, healthy and in good spirits.

Western Pacific beachcombers

Two centuries later, the classical era of beachcombing in the western Pacific began ominously in 1783, when the British East India packet Antelope was scuttled on Palau’s reefs. For three months, the crew rebuilt their ship with the help of their Palauan hosts, who lavishly treated them to food and other resources in exchange for firearms. There were other Europeans and Americans who would wash ashore in Palau, victims of shipwrecks — the Mentor, 1832; the Dash two years later; and, the Renown in 1870.

Many beachcombers became personal property of either the Reklai or the Ibedul, two competing chiefdoms that represented Melekeok and Koror, respectively. They served as “interpreter of the chief,” a loosely defined title that did little to reveal their true roles as military strategists and harbor pilots.

Beachcombers made their first appearance in the Eastern Carolines in Chuuk (formerly Truk), known as the Dreaded Hogoleu for the fierce reputation Chuukese warriors displayed; Chuuk was to be avoided at all costs. Two British seamen left Duperrey’s Coquille in 1824 to live on an island in Chuuk Lagoon, and another British seaman, William Floyd, sought refuge on Murilo three years later. None of the three lasted long in Chuuk; the two from the Coquille made their way to Guam, and Floyd was picked up by Captain Fedor von Lütke 18 months later.

Unlike Chuuk, Pohnpei (formerly Ponape) and Kosrae (formerly Kusaie) attracted a large number of Europeans during the 1830s; most of them escaped convicts or deserters from Sydney-based ships. James O’Connell, the earliest and best-known beachcomber — tattooed head to toe — lived in Pohnpei by 1830. Five years later, there were said to be 30 Englishmen living in Pohnpei, with a similar number in Kosrae.

Twilight of the era

These early beach communities were not models of interdependence; rather, murder and intrigue, alcohol and womanizing were the orders of the day. And, as increased numbers of American whaling ships made Pohnpei a port of call, desertions increased as sailors sought what they thought to be an idyllic island lifestyle.

By the 1840s in Kosrae, life for the beachcomber was riskier; Kosraeans did not tolerate the beach communities and massacred those who tried to make the island their home.

It was no wonder that Pohnpei served as the ideal island to harbor beach communities. Food supplies and resources were abundant, and the island was divided into five rival chiefdoms that competed for power. By 1850, almost 150 Europeans and Americans made Pohnpei their home (compared to four in Kosrae), earning their living as carpenters, harbor pilots, blacksmiths, and interpreters. They were also entrusted by the chiefs to serve as middlemen in business transactions between Westerners and Islanders, and were paid a percentage of the profits.

A generation later, the beachcomber era of the 1830s and ’40s was but a memory. The decline of the whaling industry, depopulation of the islands due to disease, and the increased influence of the American missionaries all contributed to the beachcomber’s demise. The American Board of Congregational Foreign Missions entered Pohnpei in 1852 and helped break the middleman monopoly established by the beachcomber while preaching Protestantism, and perhaps more importantly, helped stamp out smallpox outbreaks with vaccines.

For further reading

Day, A. Grove, ed. Melville’s South Seas: An Anthology. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1970.

Maude, H.E. “Beachcombers and Castaways.” Journal of Polynesian Society 73, no. 3 (1964): 254-293.

Micronesian Seminar. “Beachcombers, Traders and Castaways in Micronesia.” Last modified 8 May 2019.

Ralston, Caroline. “The Beach Communities.” In Pacific Islands Portraits. Edited by J.W. Davidson and Deryck Scarr. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1970.

–––. Grass Huts and Warehouses: Pacific Beach Communities of the Nineteenth Century. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1978.