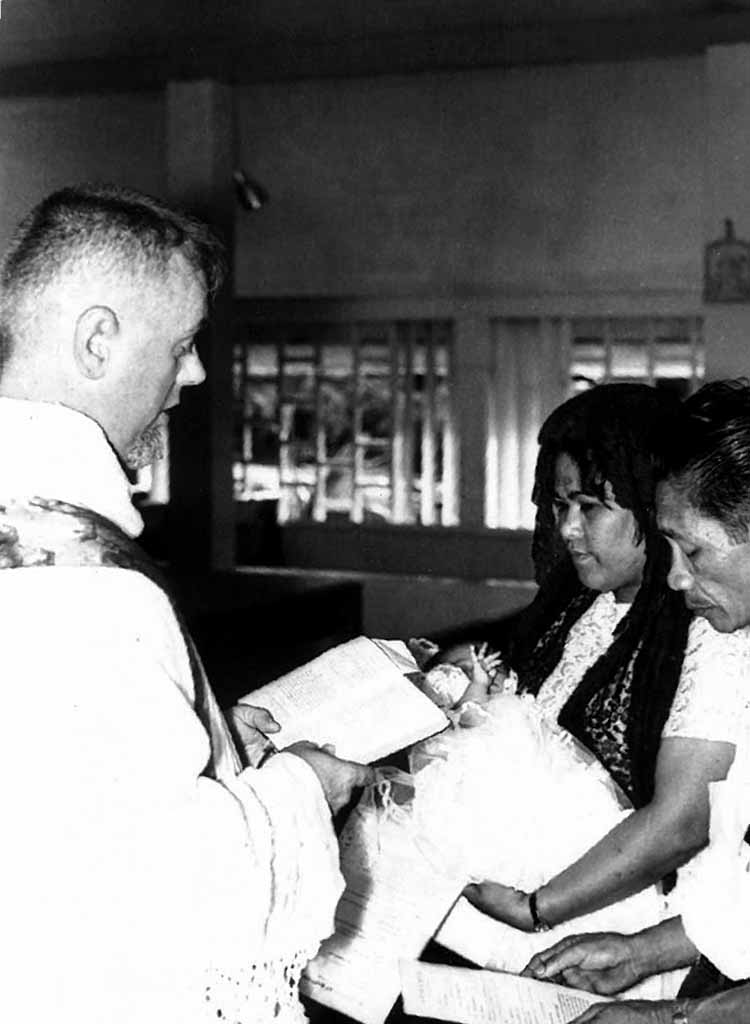

Baotismo: Baptism

Editor’s note: This entry was adapted and reprinted with permission from “Cultural Traditions,” from the Hale’-ta Series, Department of CHamoru Affairs, Government of Guam.

A family affair

In the past, picking a name for the child was a family affair. In the early matrilineal CHamoru society, the name of a newborn child comes from the mother’s clan members. But other names reflecting nature, land, sea and even types of fish were permitted. For example, Nåpu, Gådao, Tåsi, and Tåno’ and even Matagulai – probably the name of a chief – were very common in the early society. During Spanish colonization, the priests made sure newborns were given religious baptismal names such as Jose, Francisco, Maria, Guadalupe, and so on. During the American period, names such as Ashley and Marilyn, and other popular names of movie stars were given.

After the godparents (the måle’ and pari’) have been informed of the date of the baotismo from the priest, the families begin the preparation for the baotismo party. It was not unusual for the preparations to begin as soon as the mother became pregnant. The families would reserve the best produce at the ranch, fatten the pigs, hunt for pånglao (crab) and binådu (deer) to be cooked as kåddo (stew), tinala’ yan kelaguen. Atulai and mañåhak (small fish) are caught, salted and preserved as inasnen tukong; the choicest of the lemon china are squeezed and stored in bongbong (hallowed bamboo container) for the fina’denne’ (sauce). Crops such as dågu, suni and kamuti are harvested and stored in the papasåtgi (the cellar of a home); the eskomme to make the largest titiyas for the kelaguen and inasnen ti’ao is packed and stored in the låtan pritolio. A week before the celebration, the palapåla is built and jungle ferns and coconut leaves are readied for the decorations.

The godparents, members of the family, and friends finalized their offers of chenchule’ yan inayuda. Some inayuda siha come in the form of tareha – an offer of a particular type of food that is brought to the celebration. The tareha may include fina’mames, and golai åppan siha or other goods such as a basket of pugua’, pupulu, mamå’on, månnok fresko, guagua’ guihan, or a basket of fish, guagua’ gollai, or a basket of fresh vegetables, tuba and other drinks. As well, a tareha may simply be that of providing labor to build the palapåla and decorating it or bringing firewood – ningnayu – for the barbecue.

Chenchule’ from the godparents may include money alone or money combined with food, nengkanno’ måta’ pat måsa, fina’mames, or gimen (drinks). The godparents would also give a donation to the village priest who performs the baptismal rite. As well, guests give chenchule’ – money, gifts, specialty food, drinks, or their labor.

After the child has been baptized and returns home, it becomes the duty of the godparents to make sure that the mañaina bestow their special blessing on the child through mangnginge’. If ailing elders and others in the family are not able to attend the celebration, it becomes the obligation of the parents to take the child to their homes for the mangnginge’.

Nina’yan, or food given in reciprocity, occurs after the celebration. The nina’yan may consist of prepared or unprepared food, and is given to those who have given chenchule’ in whatever form. By tradition, the godparents take the largest share of the nina’yan home. The godparents’ shares are set aside before the party. In the event there isn’t enough nina’yan to go around, the family makes food including fina’mames or items that can be given away as nina’yan måta – produce from the ranch, bongbong tuba, punideran månnok, un lechon, chåda’ and so on. The process of nina’yan may continue after the celebration, the next day or throughout the week.